Across the developed world, a quiet but relentless demographic tide is reshaping societies. Plummeting birth rates and increasing longevity are creating populations with a shrinking base of working-age adults supporting a growing number of elderly citizens. Nowhere is this crisis more acute than in East Asia, particularly in Japan and South Korea, where the demographic pyramid is inverting at an unprecedented pace. In these nations, the shortage of caregivers is not a future projection; it is a daily, straining reality in homes and institutions. As traditional solutions—immigration, financial incentives for caregivers—prove insufficient or politically fraught, a technological answer is being pushed to the fore: the humanoid caregiver. Can these machines, born of silicon and code, truly address a crisis rooted in human biology, emotion, and economics? Or is this a high-tech palliative that risks deepening societal isolation even as it attempts to manage physical needs?

Japan, with its super-aged society where over 29% of the population is 65 or older, has long been the global laboratory for robotic eldercare. South Korea, projected to have the world’s highest share of elderly people by 2070, is following swiftly. In these countries, the question is not if robots will enter the care ecosystem, but how and to what effect. This analysis uses Japan and South Korea as critical case studies to examine whether humanoid robots can bridge the caregiver gap, provide meaningful companionship, and offer an economically viable path forward for nations staring down the barrel of a demographic revolution.

The Caregiver Gap: A Quantitative and Qualitative Chasm

The scale of the shortage is staggering. Japan is estimated to face a deficit of 380,000 care workers by 2025. South Korea needs hundreds of thousands more caregivers than its current system can provide. This gap is both numerical and qualitative.

The work is physically demanding, involving lifting, bathing, and transferring patients, leading to high rates of injury and burnout among human caregivers. It is also emotionally taxing and often poorly compensated, leading to high turnover and difficulty attracting new workers. The result is a system under immense strain: overworked staff, families struggling to provide care, and seniors not receiving the quality or quantity of attention they need.

Humanoid robots are proposed as a dual-force solution to this gap. First, they can directly augment the workforce by taking on specific, physically strenuous tasks. Robots like Panasonic’s Resyone (a hybrid bed-to-wheelchair robot) or RIKEN’s ROBEAR (a gentle lifting robot) are designed to perform the biomechanically risky work of patient transfer, reducing physical strain on human staff and preventing fall-related injuries. This allows human caregivers to focus on the aspects of care that require empathy, complex judgment, and emotional connection—tasks that are currently neglected due to lack of time and energy.

Beyond Physical Assistance: The Loneliness Epidemic and Cognitive Care

The demographic crisis is not merely one of physical logistics; it is a crisis of loneliness and cognitive decline. Here, the role of humanoids becomes more complex and controversial.

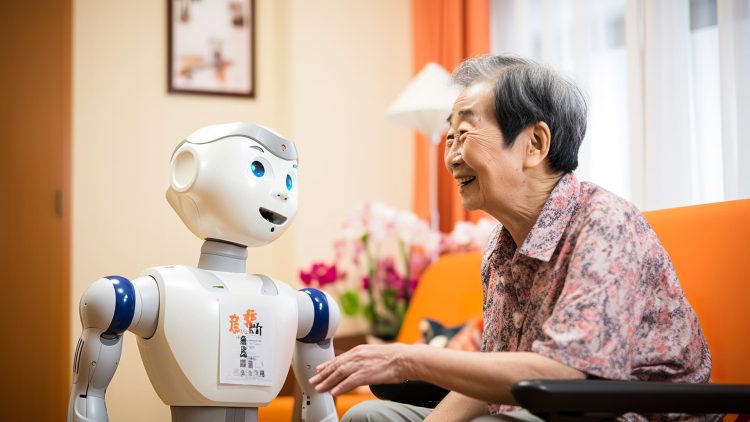

Robots like PARO, the therapeutic seal pup, have demonstrated for years that even simple, non-humanoid machines can reduce stress and improve mood in dementia patients. The next generation of humanoid robots aims to go further. They are being developed to provide cognitive stimulation through conversation, memory games, and guided reminiscence therapy. A robot with a calm, patient demeanor and access to a vast library of interactive content can engage a senior in ways a time-pressed human caregiver or a distant family member cannot.

However, this ventures directly into the psychological uncanny valley. A robot providing physical assistance is a tool. A robot providing companionship is a social actor. The ethical and psychological questions are profound: Is simulated companionship a meaningful antidote to loneliness, or a technologically sophisticated form of abandonment? For a person with dementia, who may not distinguish between the robot and a human, the interaction can provide genuine comfort. For a cognitively intact senior, the knowledge that their primary companion is a programmed entity could exacerbate feelings of societal obsolescence and isolation.

The most promising models are likely hybrid ones, where robots handle logistical and repetitive interactive tasks, thereby freeing up human time and emotional energy for deeper, authentic connection. The robot might lead a morning exercise class or facilitate a group trivia game, creating social opportunities that a human caregiver then enriches with personal touch and conversation.

Economic Imperative: The Cold Calculus of Care

For governments facing exploding healthcare and pension costs, the economic argument for robotics is compelling, albeit cold.

A detailed cost-benefit analysis must account for:

- High Upfront Costs: Research, development, and deployment of sophisticated care robots is immensely expensive.

- Long-Term Savings: This includes reduced spending on caregiver injury-related workers’ compensation, lower institutionalization rates if robots enable longer stays at home, and the containment of labor costs in a sector facing intense wage pressure due to scarcity.

- Broader Economic Benefits: By automating physically intensive tasks, the caregiving profession could be made more attractive, potentially drawing more workers. It could also allow family members (often women who leave the workforce) to remain employed, boosting overall economic productivity.

The Japanese and South Korean governments are actively funding this transition, viewing it as a strategic necessity. They are subsidizing pilot programs, setting safety standards, and fostering public-private partnerships. The calculation is clear: while the initial investment is high, the alternative—a completely overwhelmed and collapsing care system—is economically catastrophic and socially unacceptable. The robot is not just a caregiver; it is an instrument of national fiscal and social policy.

Call to Action

The demographic crisis is a tide that cannot be turned back. Humanoid robots will not “solve” aging populations, but they will become an indispensable, and inevitable, part of the care ecosystem in nations like Japan and South Korea. Their success will not be measured by whether they can replace human touch, but by how effectively they can augment and sustain it. They offer a path to alleviate the physical burden on caregivers and provide scalable, if synthetic, cognitive and social engagement.

The true test will be cultural and ethical: Can societies integrate these machines in a way that enhances human dignity rather than replacing human connection? The answer will define the quality of life for millions in their final years.

To understand the on-the-ground reality of this integration, we spoke with administrators, staff, and residents at the Silver Wing nursing home in Osaka, Japan, one of the first to pilot a full suite of humanoid and assistive robots. Their experiences—the surprises, the setbacks, and the cautious hopes—provide an invaluable real-world perspective on the future of care. Read our exclusive, in-depth interview, “Wires and Wisdom: A Month Inside Japan’s First Robot-Staffed Nursing Home.”