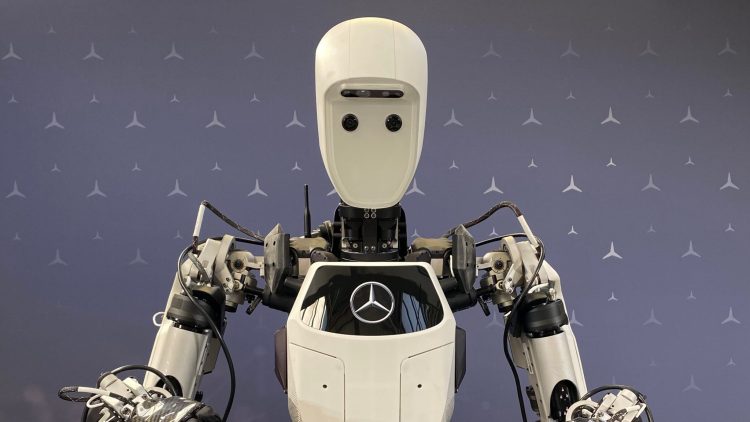

The image of a humanoid robot, a mirror of our own form, striding through a smoldering clear-cut forest or diving deep into a coral-bleached seabed, is a powerful symbol of our times. It speaks to a future where the technology born from our industrial ingenuity is harnessed to heal the wounds it helped inflict. The field of “Climate Robotics” is emerging from labs and into the wild, moving beyond simple drones and rovers to sophisticated humanoid platforms designed not just to observe, but to actively intervene in the environment. The question is no longer if robots can assist in environmental restoration, but how they will transform our capacity to repair the world’s ecosystems. This article explores the burgeoning frontier where humanoid robotics meets ecological crisis, examining the practical applications, the formidable technical challenges, and the new paradigm of human-robot collaboration in conservation.

The Labor of Restoration: From Forests to Oceans

The scale of environmental degradation is staggering. Millions of hectares of forest are lost annually, ocean plastic forms vast gyres, and coral reefs are dying at an unprecedented rate. Human efforts, while heroic, are often insufficient, dangerous, and slow. Humanoid robots are being conceived to shoulder this immense labor, performing tasks that are repetitive, physically demanding, and hazardous.

1. Replanting Forests: The Arborist Automaton

Imagine a post-wildfire landscape, charred and barren. Traditional replanting requires teams of volunteers or workers to navigate difficult, unstable terrain, carrying heavy sacks of seedlings. It’s back-breaking work with limited throughput. A humanoid robot forester, equipped with LiDAR and stereoscopic cameras, could autonomously traverse this challenging ground. Its onboard AI would analyze the soil, identify optimal planting sites based on sunlight, drainage, and proximity to other plants, and use a specialized end-effector (a robotic “hand”) to dig a hole, place a seedling, and tamp the soil. Working 24/7, a fleet of such robots could replant thousands of acres with precise, data-driven efficiency, ensuring higher survival rates for the new forest. They could also be tasked with subsequent maintenance, such as applying water or eco-friendly pesticides only where needed, minimizing waste and maximizing impact.

2. Cleaning Oceans: The Deep-Sea Custodian

The ocean floor is the ultimate sink for our plastic pollution, yet it remains largely inaccessible to human cleaners. Scuba diving is depth-limited and time-constrained. A humanoid robot diver, built to withstand immense pressures, could change this. With articulated limbs and dexterous hands, it could perform tasks that are impossible for current boxy ROVs (Remotely Operated Vehicles). It could carefully disentangle discarded fishing gear from delicate coral, sort and collect plastic debris from rocky outcrops, and even perform preliminary waste compaction for easier retrieval. Its human-like form factor allows it to use tools designed for humans, from cutters to collection nets, operating from existing ships and infrastructure with minimal adaptation.

3. Building Reefs: The Aquatic Architect

Coral reef restoration is a painstaking process where divers manually attach coral fragments to artificial structures. It is slow, expensive, and limited by weather and diver endurance. A humanoid robot, stabilized on the seabed or on a submersible platform, could take over this precise work. Its vision systems could identify optimal attachment points on a pre-placed reef structure. With a steady, unwavering arm, it could apply a biological adhesive and place the coral fragment with surgical precision, far exceeding the speed and consistency of a human diver battling currents and fatigue. Furthermore, these robots could monitor the growth of the restored reefs over time, using multispectral imaging to track coral health and detect early signs of bleaching or disease, providing a continuous stream of vital data.

The Technical Frontiers: Power and Resilience in the Wild

Deploying complex humanoids in unforgiving environments like rainforests, deserts, and the deep sea is arguably a greater challenge than sending them to a structured factory floor. Two key frontiers dominate the engineering effort: energy and ruggedness.

Energy Harvesting: The Quest for Autonomy

A robot that needs recharging every few hours is useless in a remote wilderness. Thus, energy autonomy is paramount. Engineers are exploring a multi-faceted approach:

- Solar Integration: While obvious, the challenge is in efficient integration. Flexible, high-efficiency solar panels could be embedded into the robot’s “skin” or form a backpack-like unit, allowing it to recharge during daylight operations or while stationary.

- Biomimetic Energy Harvesting: Inspired by animals, researchers are developing systems that capture energy from movement. Legged locomotion, particularly walking downhill or over rough terrain, could generate kinetic energy to be stored in supercapacitors, extending operational life.

- Thermoelectric Generators: In environments with significant temperature gradients (e.g., between the sun-baked surface and cooler ground, or in hydrothermal vent fields), thermoelectric devices could generate a trickle charge, enough for essential monitoring functions.

- Directed Energy: For deep-sea operations where sunlight cannot penetrate, novel solutions like laser-based power beaming from a surface vessel or underwater docking stations that provide wireless inductive charging are being investigated. The ultimate goal is a robot that can sustain itself for weeks or months, managing its own energy budget based on its tasks and available ambient sources.

Ruggedized Design: Built for the Elements

A factory is clean, dry, and predictable. The natural world is dirty, wet, and chaotic. A climate robot must be:

- Weatherproof and Pressure-Resistant: Sealed against dust, sand, and torrential rain for terrestrial use, and built with pressure-hardened skeletons and actuators for deep-sea missions.

- Corrosion-Resistant: Constructed from advanced materials like titanium, marine-grade stainless steels, and carbon-fiber composites to resist saltwater corrosion and biological fouling.

- Algorithmically Robust: Its software must be as resilient as its hardware. Navigation algorithms cannot rely on perfect GPS signals under dense canopy covers. Instead, they must fuse data from inertial measurement units (IMUs), LiDAR SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping), and visual odometry to navigate complex 3D terrain. Their perception systems must be trained to see through rain, snow, and murky water, distinguishing between a plastic bottle and a curious sea turtle with near-perfect accuracy.

The Collaborative Future: Human Ecologists and Robot Partners

The most successful future is not one where robots replace human ecologists, but one where they form a synergistic team, amplifying human intelligence and intent with robotic scale and endurance. This collaboration will redefine the role of the conservation scientist.

The human ecologist becomes a “mission commander.” From a central field station or even remotely, they analyze the broad-stroke data provided by satellite and aerial drones to define the objectives: “Replant this valley,” “Clean this section of the coastline,” “Begin reef construction on this shelf.” They program the high-level goals and ethical parameters into the robot fleet.

The humanoid robots become the “field crew.” They execute the commander’s plan with granular precision, operating in the hazardous zone. They collect terabytes of high-resolution, ground-truthed data—soil moisture, microplastic concentration, water temperature—and stream it back to the human. The ecologist then uses this rich dataset to adapt the strategy in real-time, perhaps noticing a patch of erosion the robots should avoid or a new coral disease that requires a different treatment.

This human-robot symbiosis creates a continuous feedback loop of action, analysis, and adaptation. It frees the ecologist from dangerous, repetitive labor, allowing them to focus on the big picture: interpreting complex ecological patterns, making strategic decisions, and advancing the science of restoration itself.

Conclusion

The vision of humanoid robots as planetary guardians is transitioning from science fiction to a tangible, if nascent, engineering pursuit. The challenges of energy, durability, and cost are significant, but the imperative to act on the climate and biodiversity crises is even greater. By designing machines that can work in the environments we have damaged, performing the physical labor of restoration at a scale and precision previously unimaginable, we are not abdicating our responsibility. Rather, we are leveraging a profound tool to fulfill it. The journey to create these robotic guardians is as much about re-engineering our relationship with nature as it is about advancing technology. It is a testament to the hope that the same creativity that built our modern world can now be directed towards its repair.